Three Monologues in Unison In Unison in Unison. Loriel Beltrán, Tomm El-Saieh, Diego Singh

CENTRAL FINE

“Three Monologues in Unison in Unison in Unison”

Loriel Beltrán, Tomm El-Saieh, Diego Singh.

October 6th-November 12th, 2024.

Opening reception, October 6th, 6-8 PM.

Seventeen years ago, I met Tomm El-Saieh and Loriel Beltrán. We were artists working in 'abstract' paintings. We considered the legacies, inventions, and impositions of the group of modernist painters that emerged in the 1940s in NYC, Latin American abstraction, music, politics, science, cinema, sociology, Glam rock, queerness, psychoanalysis. We also shared a pronounced concern with time, since our works can take years to make…to the point when we say, we can’t or won’t do anything else.

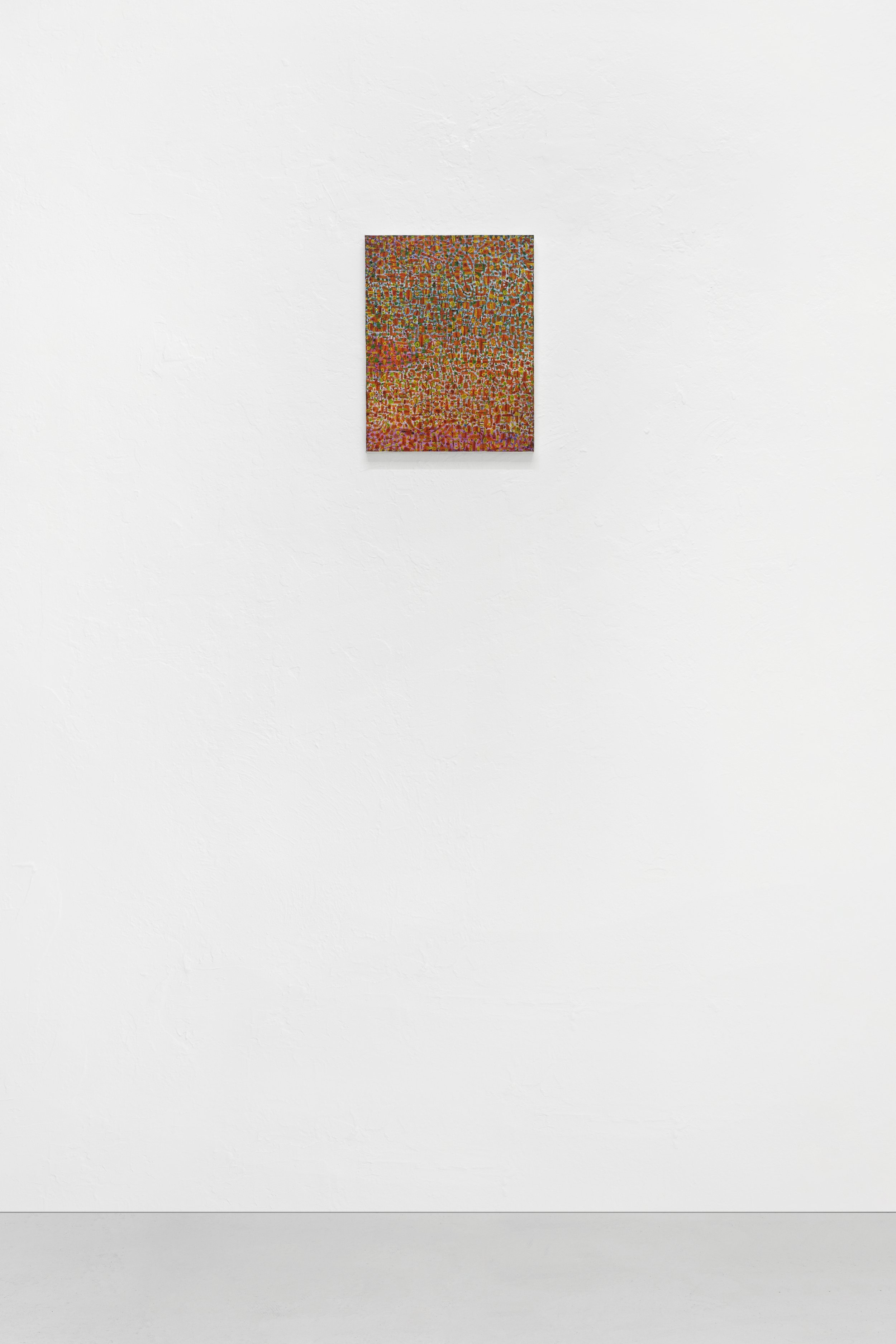

I remember some paintings that took nine years, some that I still have not 'finished'...Loriel Beltrán accumulated latex paint used to paint houses, gathering them from recycling plants, then poured them into containers, and once each layer had solidified, he cut them by hand. The process for some works took 13 years...He was excavating, like an archeologist looking for the ruins and cultural impact of what we discard, to repurpose it.

Tomm El-Saieh worked tirelessly, obsessively watching movies in his room in Miami Beach. Each mark was painted using acrylic paint, but, somehow, they looked like graphite, charcoal or pastel stains…There was a transmutation of the material in his work that confused the gaze. Each brushstroke was applied painstakingly with a ‘dry brush’, no water added. I listened to Whitney Houston's "I'm Your Baby Tonight" on repeat, while layering years of oil paint, submerging ‘finished’ paintings underneath a large coat of blue pigment...Tomm played music also on repeat; simultaneously, in the same space...I painted in his living room; he was painting in his bedroom.

Diego Singh, 2024.

Time

Loriel Beltrán uses time in his research, relies on it as a solidifying agent, and by problematizing the demand for immediacy, confronts us with the urgency of the hours, the waiting, and the unexpected. The surprise that builds slowly, over months or years, is a key element in the constitution of his body of work: After the pigment has solidified, cut, and at a later stage, composed, that’s when, for Beltrán the work is finally revealed. Until then, he is basically painting in the blind, waiting, imagining whether a layer of yellow will disappear under the weight of a green one.

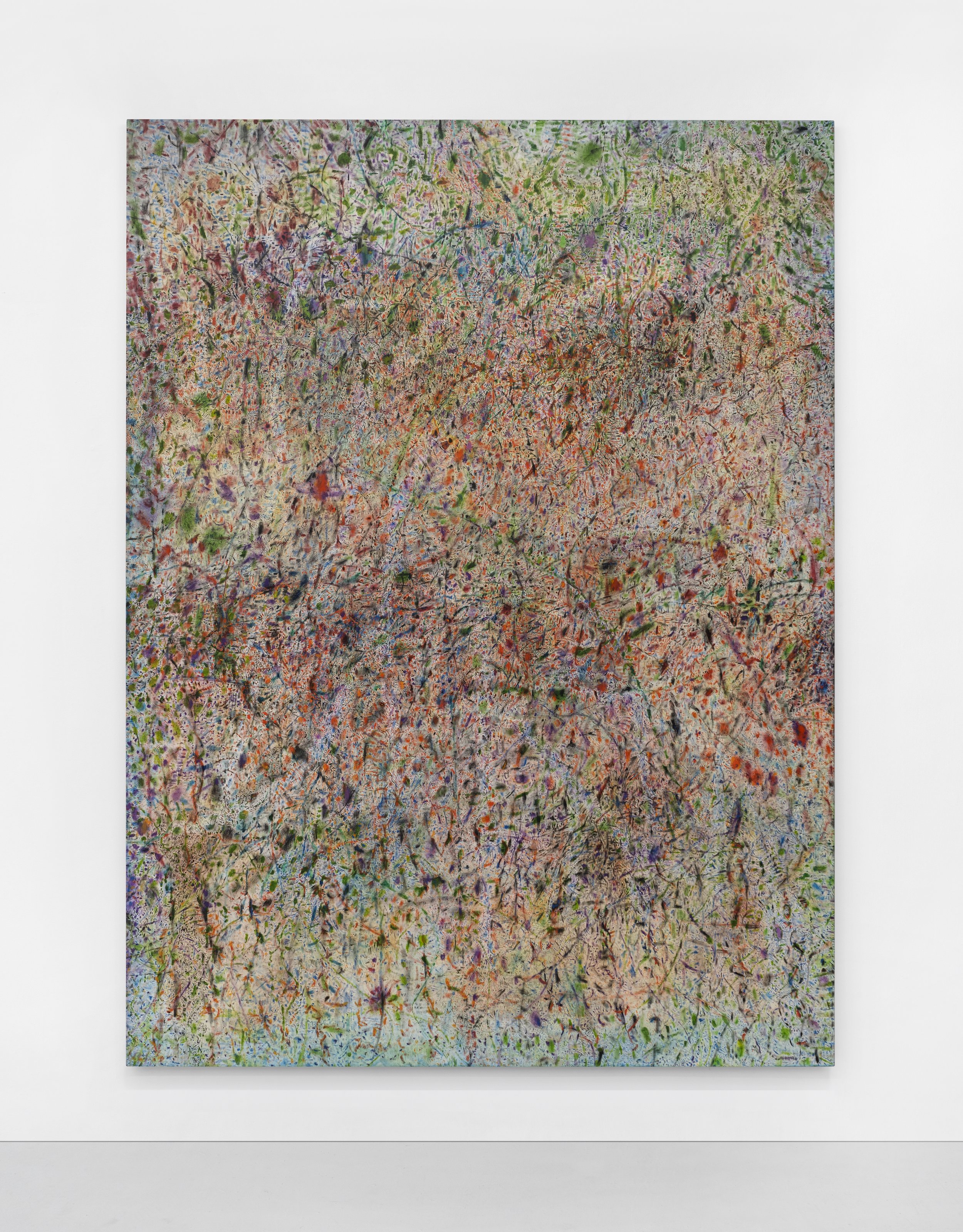

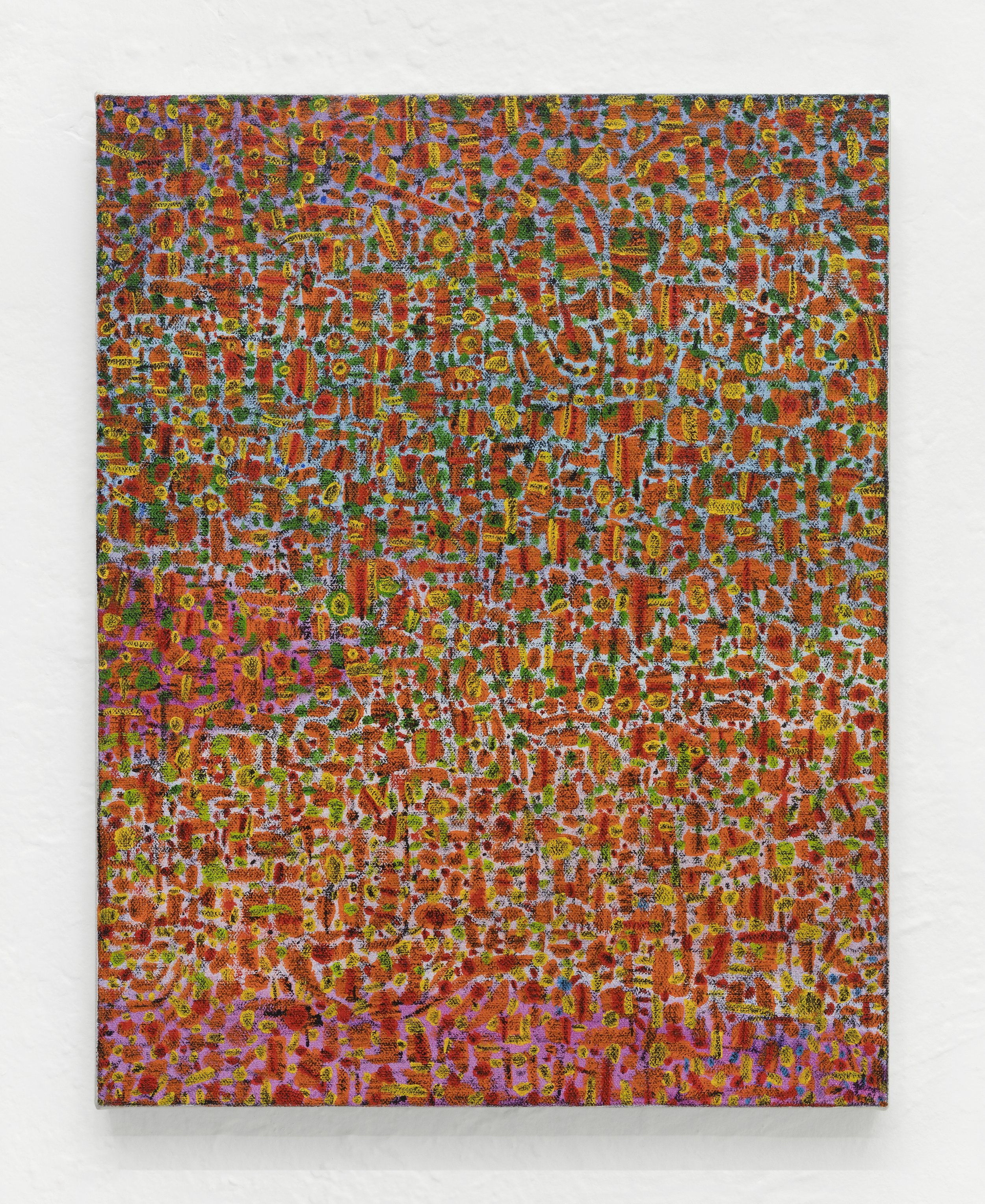

Tomm El-Saieh’s marks emphasize themselves, cross each other, obfuscate one another, as if they were presenting an inner dialogue that escapes interpretation. This process is time consuming, and sometimes can take years to complete. The ruminations of his paintings are incredibly complex, they carry within them a multiplicity of mental dialogues while El-Saieh conjures up, via non-representation, the signs of hybridization, music, history, and his own voice.

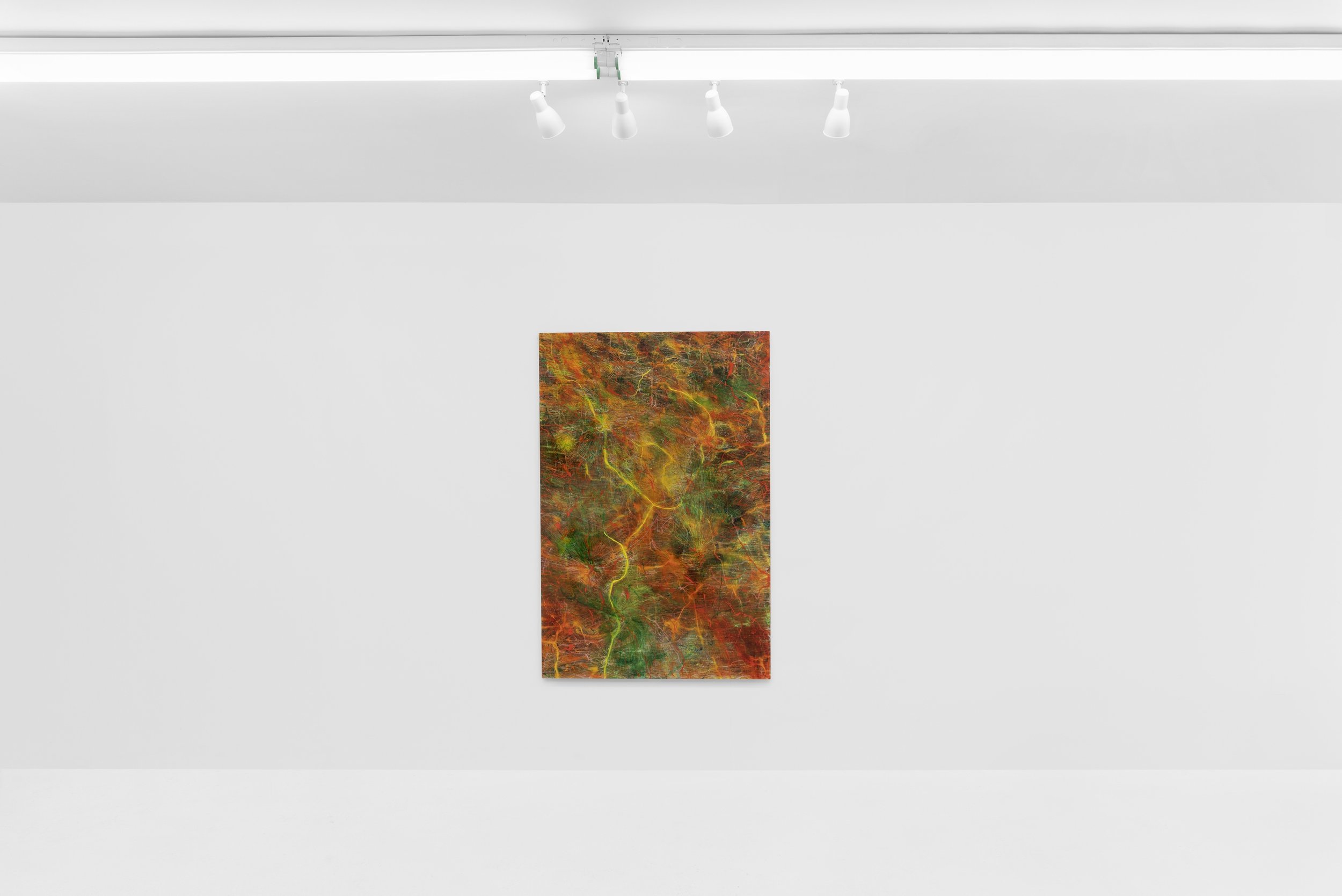

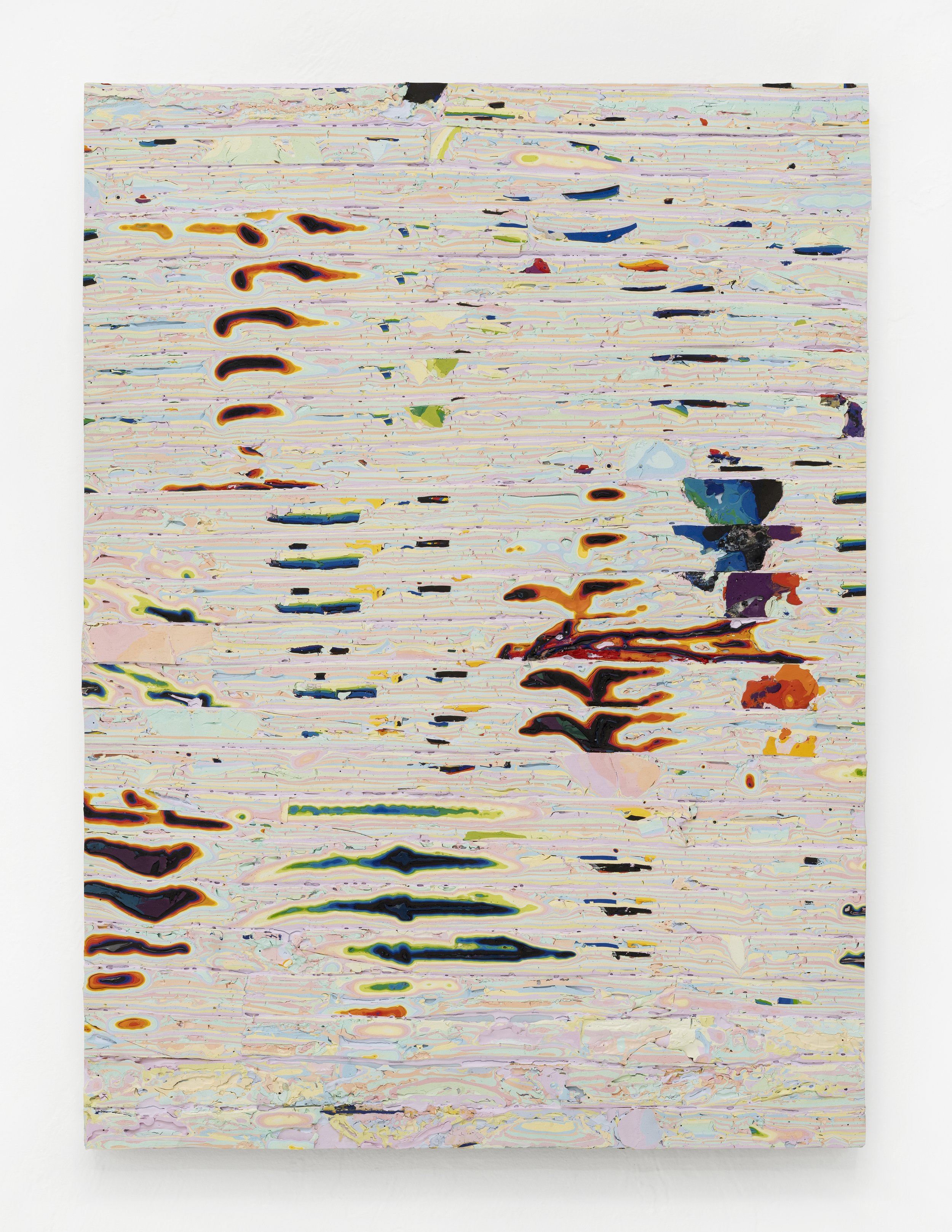

Diego Singh paints with oil paint, and his initial marks often become lost in the 20-30 coats that submerge it all. This act of ‘drowning’ the painting is related to the notion of oppression, and yet, by building up light through veiling and waiting for each transparency to dry --so that with a thin brush, he can trace lines that weave a patiently constructed surface-- Singh looks at the physical intimacies of time, queerness, their opaqueness and visibility. Queer Time, from the vantage point of heteronormativity, happens at a different pace. One cannot just defy the patriarchal system and get married whenever, in whichever country, because one has less rights, etc…Time is experienced differently in queerness. Things take way longer than for everyone else.

Years pass by, impacting the surface of these works, and what emerges are several paintings that have been buried underneath the final coat of pigment. Those traces appear and disappear, and images, like intrusive thoughts, resist the macho essentialism that insists on dumbing down the mark, by making it instantly legible, and recognizable.

Language

Another meeting point among these three monologues is the linguistic concern. In Haitian painting, the narration of historical, religious, and everyday events is omnipresent. In Tomm El-Saieh's work, that readable, linear, commemorative narration disappears. His 'writing’, his stories, can only be inferred via rhythmic vibrations and chromatic decisions. El-Saieh titles his works in Creole, evoking Haiti, speaking of its history and today-ness, through paintings abstracted from speech and legibility.

Loriel Beltrán has created alphabets, where a circle, a triangle, lines, and broken rectangles float in masses of dense color. In this personal and unintelligible speech for us, the others, one accesses a personal space where the materiality of forms and language is reconfigured to form a chain of significations that rise and fall in constant flow. No one can assist us in deciphering the broken alphabets that appear, their resonance resides in a space that is liminal and indeterminate.

In Diego Singh's work, glowing signs and musical scores appear meticulously painted, the latter using Martha Stewart’s craft brushes. Stains that resemble the look of redacted documents, highlight and obscure the skeleton of his paintings. Many shapes, underlined with a makeup gun, highlight tension as a material, in a strange light. Figures emerge, disappear, and vibrate with the intensity of color... It is a veiled speech, immersed in the watery layers of oil, that bypasses the logic of narration and paving the way for poetic invention. The silenced, the oppressed experience, is explored in a myriad of marks that look like a scribble, or complex system diagrams, and yet, as conversational as these paintings look, they remain specifically ambiguous.

Politics

In these bodies of work, can we talk about abstraction? About non-representation? Or would it be more accurate to discuss the results of exile, learning a new language, remembering and reconstructing a past that inhabits us, which we synthesize and redefine? Abstraction, as a political tool, was famously used during the 1940s by the CIA in their Operation Long Leash, confronting the social realism promoted by the Soviet Union. Today, abstraction is unavoidable: filters, the voracity of consumption, and the traffic of messages and images grant it an experiential and tangible dimension.

In these three approaches to the term ‘abstraction’, we read the records of three lives defined by common experiences: The diaspora, exile, the temporal consideration as an inherent material to the artistic act, and the possibility of recognizing, expanding, and challenging the notion of these artists respective “Parental Legacies” (Nation, gender, Father-Time, the economics of immediacy, etc.)

El-Saieh emigrated to the United States as a refugee in his childhood. Not speaking English, he felt a clash between his native tongue, Creole, and English, a newfound sound.

Exile produces a different kind of speech-painting, and in El-Saieh, the encounter between the Haitian masters of representational painting, and postwar abstraction left an indelible mark, clearly visible in his ‘abstractions’. From Andre Pierre’s punctuation and rhythmic paint application, to Morris Louis pours, or, the meditative Saint Soleil movement, founded in 1973; the diasporic imprint thrives in his body work, hybridization, then, became inescapable.

Another political aspect we can see in Tomm El-Saieh's work, lies in his refusal to adhere to the omnipresence of figuration in Haitian painting. The titles of his works allude to revolutions, wars, poetry, and oral traditions, while focusing on language’s expressive capacity, beyond descriptions. On another note, the economic and political crisis prevailing in Haiti is reflected in a certain nervousness in the application of paint, and in the economical use of pigment, shared by artists in a country where access to painting materials is significantly limited. In this sense, “Abstraction” in El-Saieh’s case, is the result of belonging and not, to various conflicting experiential and biographical backgrounds.

Loriel Beltrán was born in Venezuela, immigrating to the United States as a teenager. Over the years he has also mentioned, hybridization as a key element in his work: Gego’s understanding the line as an object, the Op and Kinetic art movement in Venezuela, all reside in the archive of memory alongside postwar artists such as Jack Whitten; or Pollock’s and Frankenthaler’s pourings and unpredictability. Aside from the past, Beltrán considers tectonic accumulations, archaeological implications, mnemonic and linguistic excavations, as well as the impact of consumption on our lives and bodies.

Recently, discarded materials from the studio, such as plastic bags and small Styrofoam cups, have been incorporated as cultural residues into his work, reflecting our consumer attitudes within his body of work. Allusions to microplastics, floating in spaces that evoke landscapes, appear in paintings that refer to prevalent ideas in art history, such as the horizon, the body, and the landscape.

Painting here is not only the result of an accumulation of sources or memories, but also becomes an experiential object, defying the cliché that abstraction cannot be political.

Diego Singh was born in Argentina during the final years of the military dictatorship that silenced and assassinated thousands of people. Known as “Los Desaparecidos” (The Disappeared Ones) thousands of intellectuals, artists, queer, non-binary, trans, political dissidents, were assassinated systematically. Many times, their bodies were covered in concrete, and dropped into the waters of El Rio de la Plata, a vast river in Argentina. These realities/ghosts/identifications appear as a constant in Singh’s work, establishing a parallel with the notion of Queerness.

In his paintings, which he calls "queer abstractions" Singh submerges what looks like neon signs of faces or bodies, underneath layers of paint, exploring the politics of visibility; while imagining the act of submerging that neon sign under water, short-circuiting it all.

The outline of such faces is always rendered in ¾ profile --as the photographs of National Identification Documents were demanded in Argentina. From this starting point, pictorial games can be activated: Delicate lines painted in oil, float like paths/veins/hair/threads unraveling over these faces-structures. Through these strategies, that point to queerness’ power to destabilize normative readings, Singh’s paintings refuse essentializing unifications, in favor of relational models for being together in difference, [i] making overloaded, overburdened paintings populated by signs, in multiple and ambivalent ways.

Color

In Loriel Beltrán paintings color has a multifaceted role. He researches it intensely, approaching it from an analysis of chromatic forces, thinking about its relation to light, observing it as a byproduct of various industries, a sign that points to emotional and art historical records, something invisible that becomes tactile, while generating an interplay between the mechanical, the organic, and the meditative. A painting can recall a sunset, punctuated by white shapes, that on close inspection reveal cups made of styrofoam, or a dramatic composition in greens, blues, flesh tones that transport the eye straight into the Sistine Chapel.

Tomm El-Saieh’s use of color is personal, while also reflecting elements of Haitian identity. His low-contrast compositions introduce a sense of unease, a muted light, contrasted with the brighter, more saturated colors seen in depictions of animals, nature, or technology. One could say that the chromatic tendency of traditional Haitian painting negotiates its intricacies with the psychological aspect of perception, and the complexities of color theory.

Diego Singh’s paintings insist on an exuberant handling of color, or the ‘unnatural’ vibrancy of what culturally is referred to as a flaming queerness. Singh points to the re-presentation of the construction of gender, as a space of play and tension. His paintings emanate a luminescence that is built from a ground that is usually painted in black or gray. In his paintings, we see color acting as a political and personal agent, a reverberation that emerges from darkness outwards in an explosive and ‘unnatural’ way. His palette never has the ‘organic’ or 'natural look’ (beiges, browns); but rather they have the color of the artificial, the saturation of a flaming peacock, and the fluorescent bug.

Loriel Beltrán was born in Caracas, Venzuela and earned his B.F.A from the New World School of the Arts, Miami, FL. Recent solo exhibitions of his work include Over the Sun, Under the Earth (2022), CENTRAL FINE, Miami, FL; Constructed Color, Museum of Art and Design, Miami, FL (2021); and New Old Paintings, CENTRAL FINE, Miami, FL (2020), Beltrán’s work has also been exhibited in a number of significant group exhibitions, including Cut: Abstraction in the U.S. from the 1970s to the Present, Frost Art Museum, Miami, FL (2019); GUCCIVUITTON, Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, Miami, FL (2015); T.A.Z., Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, FL (2015); Global Positioning Systems: Urban Imaginaries, Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami, FL (2014); and Liquid Matter, The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, PA (2011).

Beltrán was also a co-founder and co-director of the artist-run gallery and collective Noguchi Breton (formerly GUCCIVUITTON). His work is included in several notable private and public collections, including the de la Cruz Collection, Miami FL; Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, Miami, FL; and Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami, FL, among others.

Tomm El-Saieh was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. In January 2022, El-Saieh’s work was featured in a year-long exhibition at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, curated by Robert Wiesenberger, Associate Curator of Contemporary Projects. In 2018 his work was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Miami, curated by Alex Gartenfeld and Stephanie Seidel. The same year El-Saieh was included in the New Museum’s 2018 Triennial: Songs for Sabotage in New York. Additional noteworthy exhibitions include solo presentations in 2015 and 2019 at CENTRAL FINE, Miami.

Parallel to his artistic practice are El-Saieh’s curatorial endeavors that focus on historical and contemporary Haitian art. El Saieh’s work is part of the permanent collection of the ICA Miami; Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin; Rubell Family Collection, Miami; Rice University, Texas, among many others.

Diego Singh was born in Argentina. He has exhibited his work at Luhring Augustine, the ICA Miami, FL; Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, CA; Pérez Art Museum Miami, FL; Fondazione Malvina Menegaz, Castelbasso, Italy; Braverman Gallery, Tel-Aviv, Israel; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo, Brazil; Palazzo Fruscione, Salerno, Italy; Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo, Japan; Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami, FL; Various Small Fires, Los Angeles, CA; Galleria Macca, Cagliari; and the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, FL, among others.

He is the founder of CENTRAL FINE, in Miami Beach. Singh has acted as regional correspondent for the Future Generation Award, presented by the Pinchuk Foundation in Ukraine on many occasions. Singh was awarded the Knight Foundation award in 2019 and 2015. His work is included in the permanent collections of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, The Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), The Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, among other institutions.

[i] Lancaster, Lex Morgan: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art, pp 137. Duke University Press, 2022.