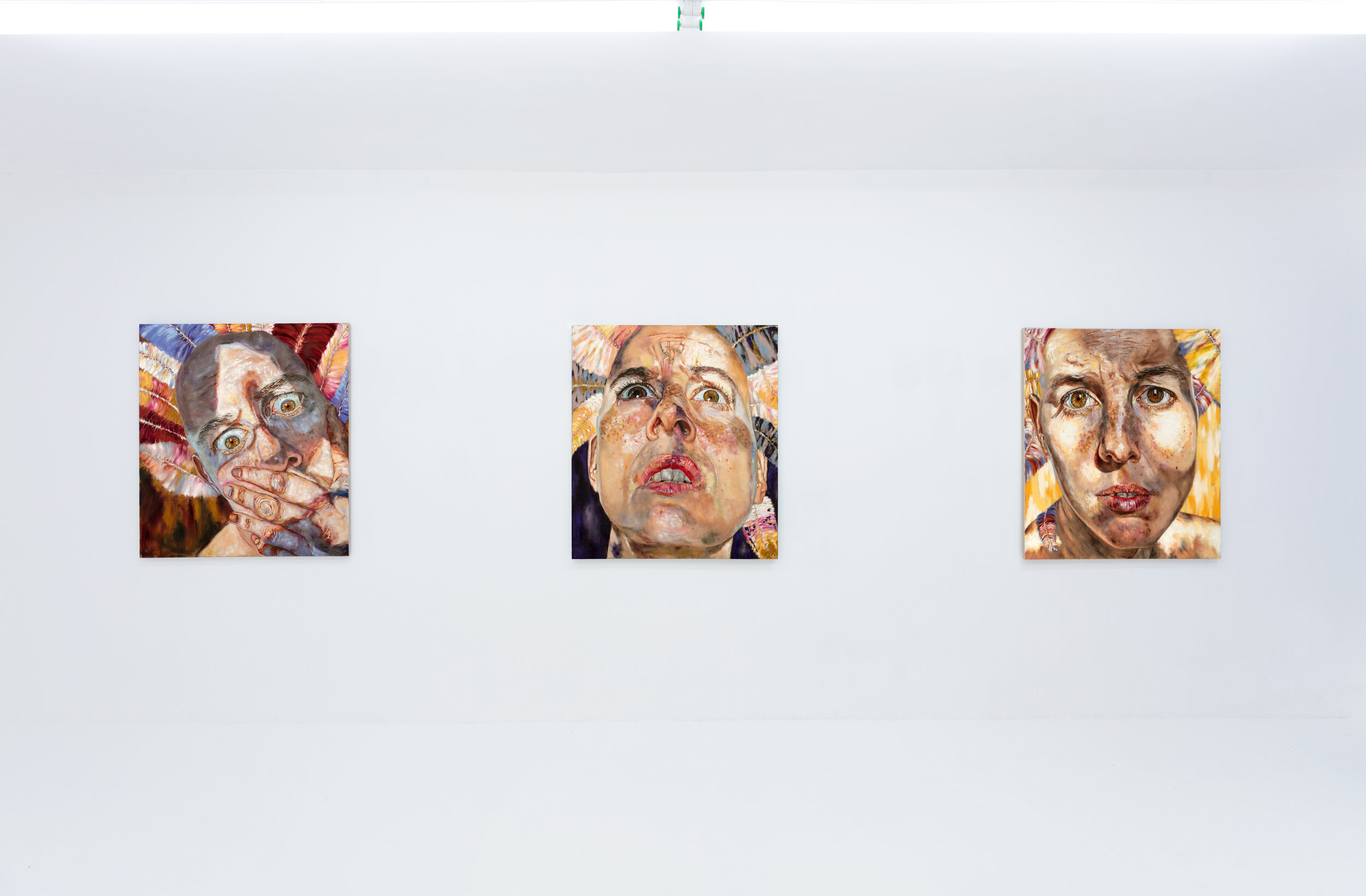

CONSTANZA SCHAFFNER. CONSTANZA

September 13- October 18, 2020

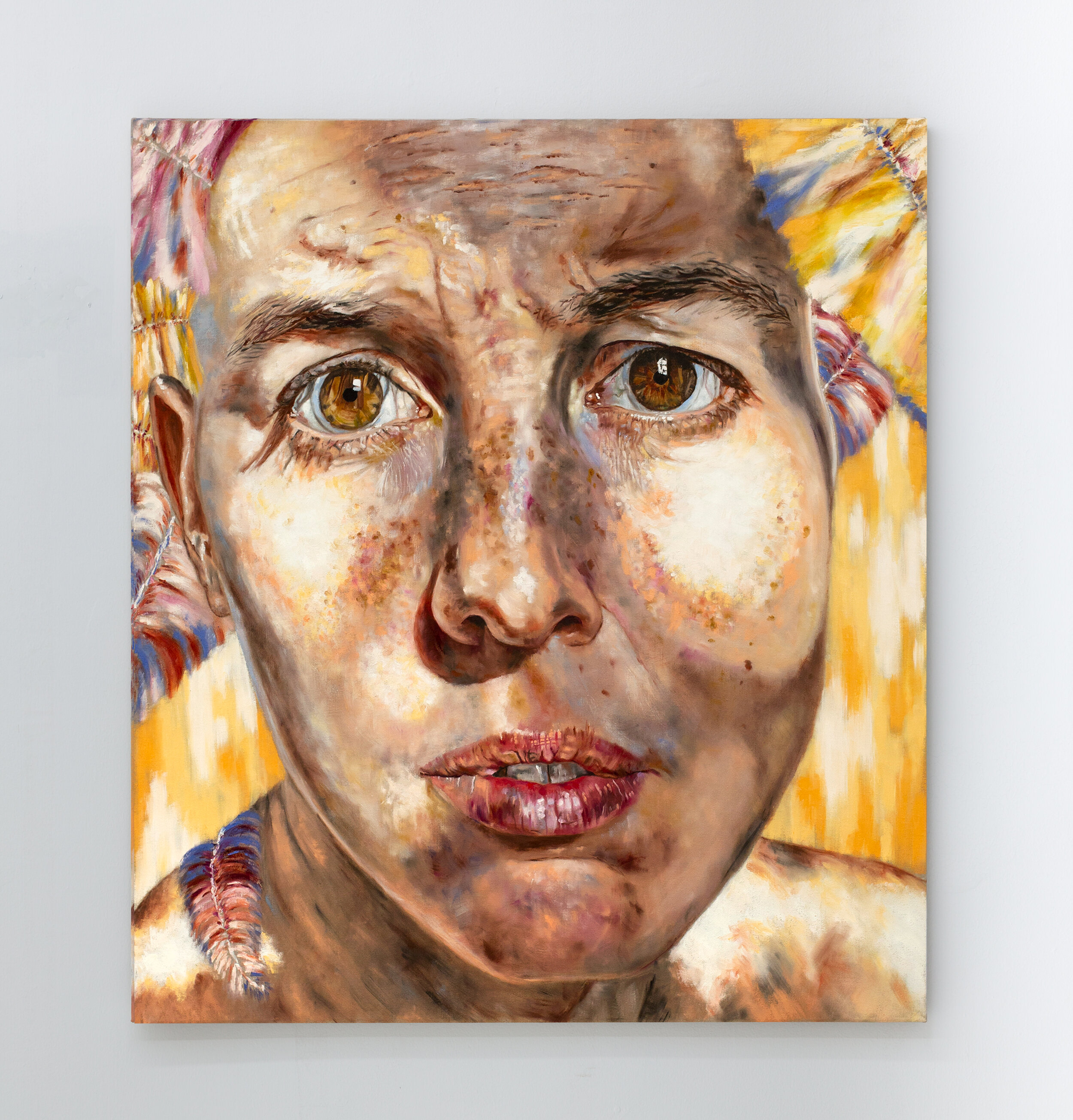

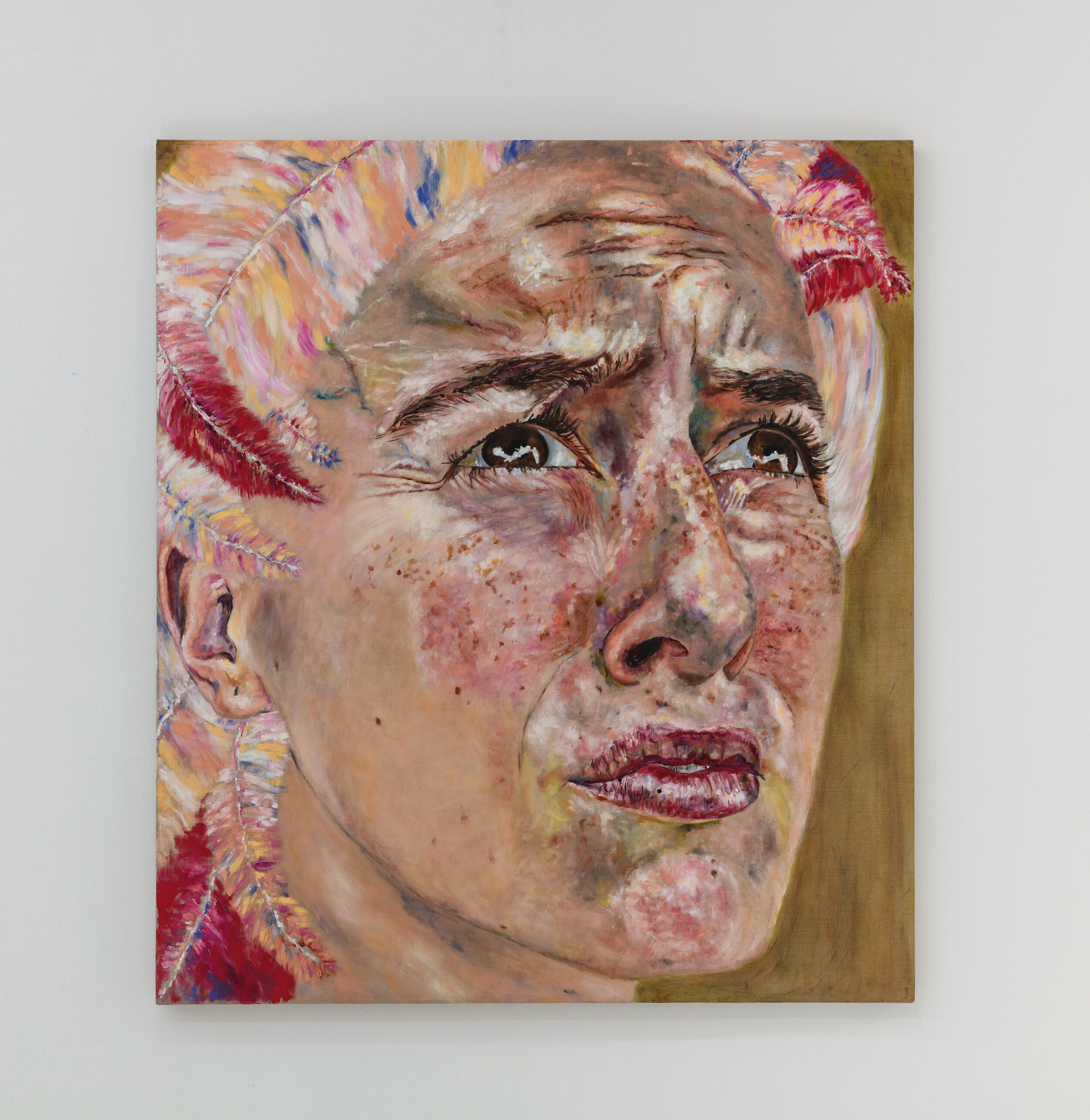

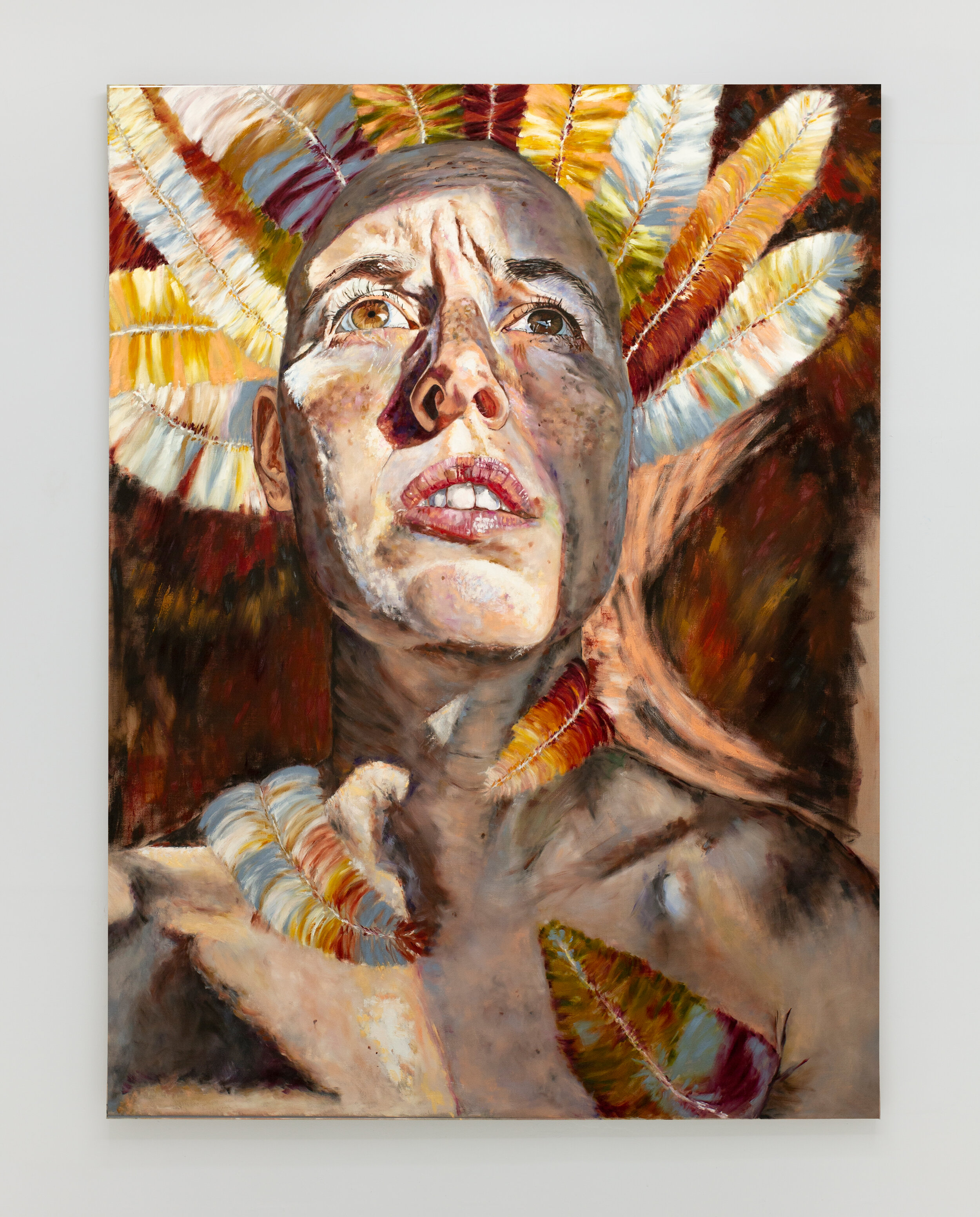

Constanza Schaffner’s self-portraits appear as narrations without clear plots, presenting a skin/texture that isn’t smoothened over by filters, but rather informed by nature and culture, symbolically articulating otherness. Her work echoes opera and cinema, as an early inspiration for Constanza was found, for instance, in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s use of close-ups in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1924).

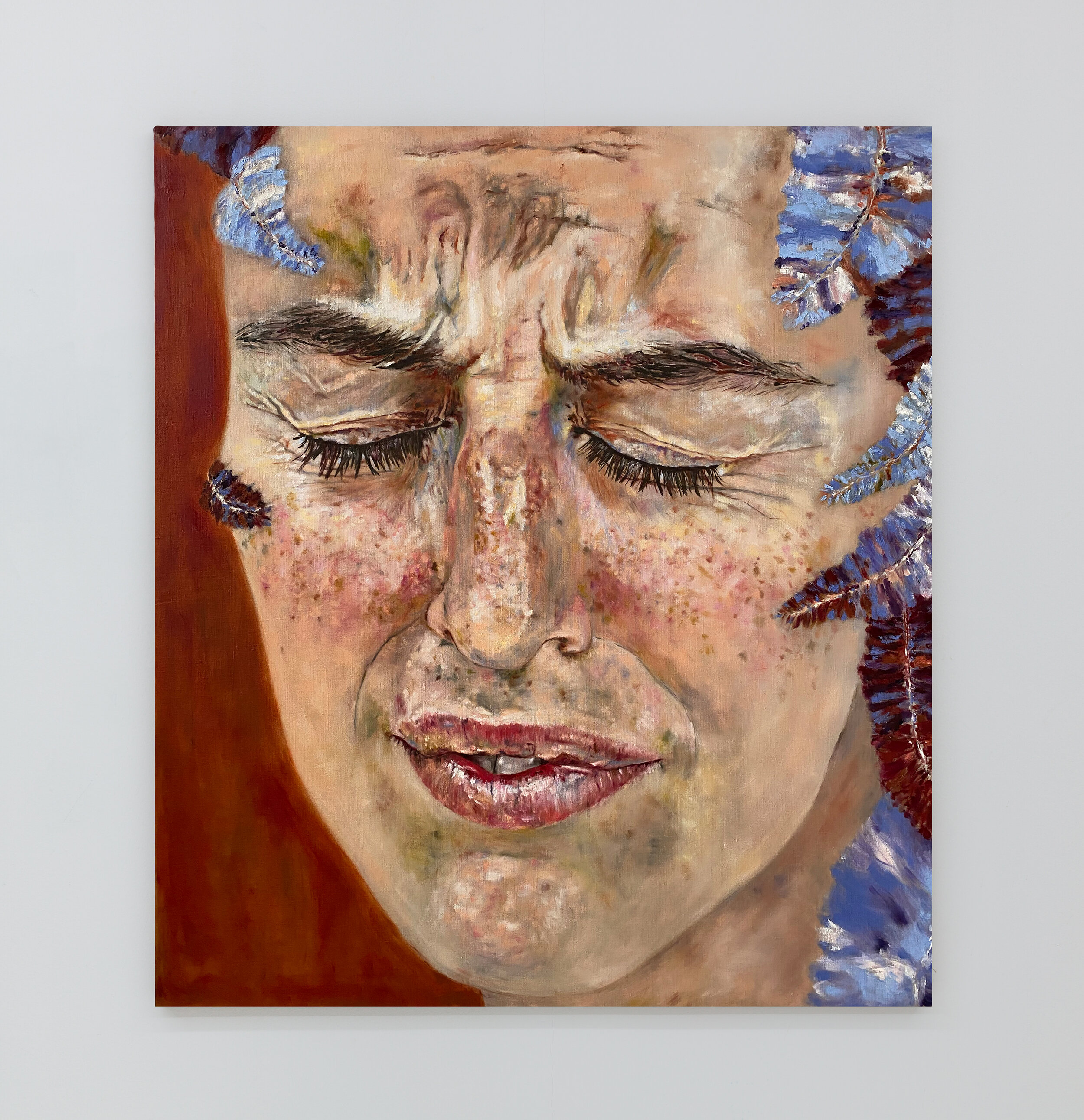

Schaffner’s self-portraits seem to look out, or gaze inwards, opposing the centrality of narcissism by opening themselves up to mutations, as feathers grow, and patterns from nature appear inscribed as a wrinkle. As Schaffner points: I also emphasized the creases in the skin and knuckles, by painting small geometrical and abstract compositions in each of them, thinking about the shapes of plants, flowers, or the barks of trees. I was inspired by Dante’s Forest of the Suicides, a circle of Hell in the Divine Comedy in which those who have committed suicide are punished with metamorphosing into branches of trees for the rest of eternity.

The titles of her paintings avoid locking down the reading of the self-portrait as one, by constructing various scenarios –one painting is Adentro Hay Algo (There’s Something Inside), another is It Never Came, or, there’s Siesta (Nap), in which Constanza closes her eyes, hit by a harsh light, forcing herself (perhaps) to sleep, or to remember something… (The siesta time is a liminal moment in Argentina, and particularly in provinces such as Entre Ríos, were Schaffner partly grew up. During the hours between 1-4 PM businesses close, and people go to sleep, while children are abducted by elfs –as legends would have it– in plain daylight.)

In Entre Ríos, after the siesta, once a year and for days, people celebrate the Carnaval de Gualeguaychú, wearing costumes sporting feathers and bright colors, rhythmically trespassing the rigidness and the bureaucracy of the collective Super Ego.

What follows are some of Schaffner’s notes on feathers, Magical Realism, portraiture, etc.-

Feathers

One could think of the feathers in the self-portraits as adornment, fashion, camp, in terms of the Lacanian idea of the function of art as that of seducing the gaze. In particular, Lacan talks of the function of painting as that of being a dompte-regard, a taming of the gaze:

“The painter gives something to the person who must stand in front of his painting which, in part, at least, might be summed up thus –‘You want to see? Well, take a look at this!’ He gives something for the eye to feed on, but he invites the person to whom this picture is presented to lay down his gaze there as one lays down one’s weapons.”

This Lacanian idea is connected to the work of Roger Caillois. Caillois developed what he called ‘diagonal sciences,’ establishing connections between an array of areas of knowledge and, most notably, between the animal world –of instinct– and the human world –of freedom. In Méduse et Cie, he theorized art as the human analogous to the animal phenomenon of mimicry, which includes different strategies to counteract the aggressor’s gaze: travesty, when the animal tries to appear as a representative of another species; camouflage, when the animal manages to be confused with its environment; and intimidation, when the animal paralyses or frightens its aggressor. Could we then maybe think of the feathers as mimicry, as simultaneously travesty, camouflage and intimidation –all strategies to tame the gaze? I expose myself but I also protect myself.

Magical Realism

The feathers in the paintings also point towards the idea of metamorphosis into a bird. I use imagery from Latin American symbolism and mythology and repurpose it as utopia, as images of hope for a better future –a future of more symbiosis with nature. As utopian dream-symbols, the portraits combine despair with hope.

Magical Realist writers also subverted sacred and secular colonial myths, by repurposing them into expressions of resistance and revolution –against colonizing modernity and a reactionary appropriation of these myths by the Church.

Realismo Mágico is both connected to and at odds with Surrealism. As Michael Taussig explains, its founder, Alejo Carpentier, frequented the Surrealist circle in Paris but, precisely, reacted against it: he found it too heavy-handed, in its effort to create magic by taking forms from dream or decontextualizing artifacts from ‘primitive’ civilizations. In his return from Paris to Haití in 1943, Carpentier realized he didn’t need the artifacts, because “there in the streets and the fields and the history of Haiti the marvelously real was staring him in the face. There it was lived. There is was culture, marvelous yet ordinary.” 2 He discovered lo real maravilloso, the ordinariness of the extraordinary in Latin America.

Notes on self-production and self-alienation

1.-Self-portrait: Already Nietzsche noticed that it is better to be a work of art than to make art (The Birth of Tragedy, via Boris Groys).

2.-The face. The face is the place where the struggle for truth happens (Agamben). The face is the passion for revelation.

3.-I produce myself as I constantly question and declare myself: my poiesis is my poetics.

4.-I place the self at the center of the artistic production, only to declare it an artificial construction, challenging the myth of unity. I turn myself into an object, I alienate myself. Rimbaud: “The I is another.”

Schaffner’s work, then, could be considered both centrally and laterally, as the self-portrait can be recognized as one, but also as embodying the otherness of the other, alterity. Her approach to Painting actively defies the optimization of texts/surfaces, making contact with the ‘negativity’ attributed to whatever escapes the censorship that insists on Flattening and on the elimination of subjectivities.

Constanza Schaffner lives and works in Brooklyn, NY, and was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1989. She studied Philosophy at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. She won an Argentinian national award for academic merit and, in 2013, moved to NYC to pursue a PhD in the Department of Comparative Literature of NYU, with a full fellowship. Schaffner taught at NYU and gained her MA, while at the same time pursuing a studio practice. Self-taught, her practice encompasses painting, drawing and collage, and stems from her realization of the limits of philosophy for the comprehension of reality, in an attempt to instead “open” meaning, rather than force it into rational-linguistic categories. Schaffner had her exhibition debut at the artist-run project space Plymouth Rock in Zurich, Switzerland, in 2018. She is writing her PhD dissertation –directed by Ara Merjian and Boris Groys – titled “The Sacred as Resistance and Revolt: Bloch, Pasolini, Bresson,” which she plans to turn into a book. Her work is now part of the Hall Foundation, and this is her first solo presentation at CENTRAL FINE.

1 Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis (New York: Norton, 1978), p. 111.

2 Michael Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: a Study In Terror and Healing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 166.

Constanza Schaffner’s notes in Italics, Brooklyn, 2020

Diego Singh’s notes in Arial Normal, Miami Beach, 2020